A dream shared by loads of children is to someday be a national champion, even win the Olympic gold. For Forrest Craig, it was figure skating, and his journey began when he was seven. “I had no comprehension of the significance of national stature yet alone the Olympic Games”, he would later recall.

He began skating playing ice hockey at the Raydines Ice Rink in San Anselmo. He became a league winning goalie for most saves recorded in a given season but when Forrest turned 11 years old, he remembers, “I wanted to keep my front teeth, so I switched to figure skating!” In 1966, along with his sister, Lisa Ann, he began skating seriously. When most of their classmates were still are in bed, He and his sister would rise at 4:15 AM and his mother, Frances Leilani, would drive them to Berkeley Ice Land, where they would begin practice at 6:00 AM. Competing as members of the St. Moritz Skating Club, they were fortunate to be trained by former Olympic gold medalist and national champion Tim Brown.

That summer, they were invited by the Squaw Valley Figure Club to train at the Blyth Arena in Squaw Valley – the site of the 1960 Winter Olympic Games. Their coaches were James and Barbara Grogan, also Olympic gold medalists. James “Jimmy” Grogan was the 1960 US men’s gold medalist and Barbara Wagner and her pair skating partner Robert Paul were the gold medalists from Canada. “They taught me the values of discipline, commitment and work ethic, along with the importance of family”, Forrest remembers. “They also helped me understand what it would take to become a champion- the countless hours of hard work practicing on the ice and the significant social sacrifices that I’d need to make by missing interaction with my peers at school”.

Behind every would-be Olympic figure skater is the “Skating Parent”, who acts as chauffeur, manager and cheerleader. For years, their mother would sit on cold, metal seats, praying and applauding during high-stakes competitions in which a two-minute performance can make or break a skater’s world ranking. “She was always there.”

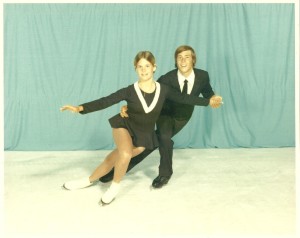

But it soon became clear that that commuting back and forth to the skating rink was a strain on Frances. So in the summer of 1967, Lisa and Forrest moved to Squaw Valley to live with local families, go to school and train. “We joined the Squaw Valley Figure Skating Club (which trained such notable Olympic medal winners as Charlie Tickner, Scott Hamilton, Dorothy Hamill and Peggy Fleming). My life was now focused on skating both in the single men’s category and in the pairs competition, with Lisa as my partner. We practiced 2 1/2 hours in the morning before school and 2-3 hours in the afternoon every weekday at Blyth Arena. We practiced 6-8 hours on Saturday and had Sunday off, usually doing homework as we were not allowed to snow or water ski for fear of getting hurt.”

1967 saw Forrest’s star rise. He would win the gold medal at the Central Pacific Championship and bronze medal at the Pacific Coast Western States Championship. This ranking qualified him for the 1968 National Figure Skating Championships in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The national championships had twelve other competitors: three from each of the four regions around the country. “After the intense compulsory figures were judged (no longer performed in national competition), I was in third place. After the final free-style (free skate) competition I dropped to a disappointing fourth place. This was the first time that I felt the political nature of judged competition as many believed I had scored better. However, my family and my coaches felt that I had made myself known and was now in the hunt for a future national title and potential Olympic bid.”

Forrest continued skating competitively for the next few years. A turning point came in the fall of 1970 when he moved back to the Bay Area. Should he continue skating for the next several years, hoping for a bid at the national championships? He chose to give it one more year and in the summer of 1971, he and Lisa attended the Sun Valley Invitational championships in Idaho and did well skating in the pair competition. They then went to Colorado Springs to train at the famous Broadmoor Ice Arena. “But competition that year was a disaster. To this day I believe it was not returning to the team at Squaw Valley and the high caliber of coaching, support and focus that were the primary causes of my demise.” After competition ended that year, he chose to hang up his skates.

“This was of course a tough decision for me as well as those that supported me through the years and potential future bid.

I realized that my skating and Olympic dream were no longer in my heart. I wanted to run cross country with my school buddies, snow and water ski, party, and do things that I couldn’t do as a high level competitor. I wanted to further my social and athletic skills and endeavors. I wanted to enjoy college as other mates were planning to do.

“But skating was an opportunity of a lifetime. I grew up fast and traveled the country, a gift few teenagers are rarely afforded. For this I am eternally grateful. Skating fills us with a sense of euphoria, accomplishment and inspiration. It is the boundless frozen canvas where dreams are etched and worries are swept away. It is the home that travels to wherever ice exists.”

Source: 2014 personal interview by David E. Good.