Born: February 22, 1857; Oswego, New York

Death: June 14, 1939; St. Helena, California

John Hoffman Wheeler was born February 22, 1857 in Oswego, located on Lake Ontario in the northwestern corner of New York. The son of Charles and Caroline Wheeler, John was born into a family of entrepreneurial pioneers with a passion and quintessential gift for agriculture and viticulture. Charles Wheeler and friend Charles Krug – just up the valley from the Wheeler farm, were best described as the “who’s who” among Napa Valley vintners, businessmen and pioneers of the time. It can also be said that John Hoffman Wheeler was a self-made early California entrepreneur.[1]

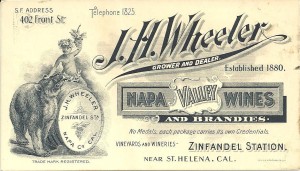

At the young age of two, his mother, Caroline, died in Oswego. Charles moved John and his brother, Rollo, west to Vallejo in 1867 and in 1869, purchased property two miles south of St. Helena at Pine Station, later known as Bell Station and Zinfandel Station, and today known as Zinfandel Lane. At this location he built a stone winery on the family farm known as Wheeler Farms.

John and his brother worked the family farm until 1875, when he entered the University of California, Berkeley (the first graduating class was in 1873). A bright scholar, he studied chemistry, specializing in pesticides for the grape industry, experimenting on the vineyards surrounding the campus. He was said to have been great at doing things outside of the curriculum. John was mentored by Professor Eugene Hilgard, who today is considered the father of modern soil science in the United States. Together they conducted experiments on the University grounds using carbon bisulphide (now known as carbon disulfide) to kill ground squirrels. Wheeler published his findings from experiments in a University bulletin in April, 1878.[2]

At the time he graduated from Berkeley, the grape growers of the world were threatened with a plague of plant lice called phylloxera, which was devastating their vineyards. In France, they discovered that the plant lice could be controlled with bisulfide gas, but the California growers could not afford the imported price of between 50¢ and $1.00 per pound. Wheeler experimented with making the carbon bisulfide in a small factory on the bay shore of Berkeley. He founded the San Francisco Sulphur Company; soon turning out commercial grade bisulphide at prices around 13¢ per pound, making it available to vintners as well as general stores for pest killing purposes.[3]

In 1879, John married Frances V. Jones of Chico. Their four children were Ella Cornelia, Elliott, Rollo Clark and Ysabel. They fondly referred to their father as “Papa John” and their mother as “Mama Frank” and those names have stuck to the current day. In 1881, John H. Wheeler was appointed by the governor of California as the first Secretary of the State Board of Viticulture and served as its executive head in 1888.The report of the first Fruit Growers Convention was written by Wheeler and was published by the Pacific Rural Press. The report was said to have been “a mine of horticulture information because it preserves the names and declared purposes of the men who were leaders in laying the foundations for the great achievements of the present day.”[4]

In 1889, John’s brother Rollo, who had been managing the winery and orchards back in the Napa Valley, was kicked in the head by his horse and died. John returned and to take his brother’s place with his father. Growing grapes and wine making were the major activities of Wheeler Farms until the Prohibition Era ended the demand for alcoholic products. The farm then expanded to produce walnuts and prunes. Although the winery has since been torn down, the original craftsman style home still stands on the west side of Highway 129, just south of the railroad tracks at Zinfandel Lane.

Meanwhile, the San Francisco Sulphur Company was growing rapidly and expanded into making bone meal fertilizers and other agricultural products, relocating to Seventh Street and Snyder Avenue in West Berkeley. A competing chemist across the Bay in San Francisco, John Stauffer, took note and the two decided to merge their companies. Stauffer turned to banker Christian de Guigne (a founder of the Bank of California, now Union Bank) for advice and financial assistance. Although the shirt-sleeved working chemist and the elegant older Frenchborn banker had very different lifestyles, they held identical views on thrift, integrity, and the value of hard work. Not only did de Guigne encourage the merger, he decided to become a part of the company.[5]

On July 19, 1895 the Stauffer Chemical Company was incorporated under California Law with a capitalization of $300,000. Christian de Guigne became Chairman, John Wheeler, Vice President and John Stauffer, Secretary. The three men ran the company for 37 years in great harmony and with outstanding success.[6]

Stauffer Chemical Company grew from its family owned and operated firm to a multinational, multi-billion dollar corporation, going public on the New York Stock Exchange in 1954. John Wheeler served as Vice President of the Stauffer Chemical Company from 1895 until his death in 1939. His second son, Rollo Clark, took his place as Vice President on Stauffer’s Board of Directors until his passing in 1962.[7]

Of John Wheeler, it was later stated that “Simply a university student had the sense and sand to do something which prescribed studies did not require of him, but which practical operation made necessary to agriculture and ministering to the need made profitable to the originator”. According to a published University bulletin, “Although he has done many original stunts on his fine fruit far in the Napa Valley, we always think of him as the youth who jumped a lecture course on the feasibility of perfume farming in California, and built a bisulphide joint on the bay shore which, though not much bigger than a Dutch oven, made more smell than all the perfume of Araby the Blest, and was the foundation of the largest business of carbon bisulphide manufacturer in California.” The university author complimented the young entrepreneur with the closing remark “We like young men when they do things their teachers do not know enough to teach them to do!”[8]

[1] Napa Register, date unknown.

[2] University of California Bulletin, April 1878.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Pacific Rural Press, vol. 31, no. 10, March 1886.

[5] Stauffer News, Stauffer Chemical Company, 1977.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.