Coming soon!

Author: Admin

Sunnyside Farm, Sonoma

Coming soon!

Stauffer Chemical Company

When John Stauffer arrived in San Francisco in 1881, the city was a magnet for talented and ambitious young men. The discovery of gold in the mountains west of the Continental Divide and the influx of the 49ers had transformed San Francisco from a sleepy village to a city of fabled opportunity. Stauffer came to sell heavy chemicals for a Belgian company. For the City’s manufacturers, and the farmers and grape growers on its outskirts, rail and sea freights made chemicals imported from the East coast or Europe prohibitively expensive. Stauffer had noted, soon after he arrived, that grain ships taking western wheat to England, usually returned in ballast, loaded down with white cliffstone from the chalk cliffs of Dover. When the ships took on new cargo, the cliffstone was simply dumped overboard. If he could find a way to grind the cliffstone – much in demand locally for whitewash and other uses-he could sell it for half the imported price.[i]

It didn’t take long for him to go into business for himself. With the help of a countryman, Joseph Mayer of Hamburg, who owned a plot of land at North beach in San Francisco, the financial assistance of an elegant young French banker – Christian de Guigne I, and two shiploads of Dover cliffstone, he began the entrepreneurial journey that would become Stauffer Chemical Company.[ii]

With his plant in North Beach, the enterprising Stauffer looked around for more opportunities. He made friends in the local chemical industry, One of these friends was the earnest young chemist John H. Wheeler, who by then was producing carbon bisulfide, along with other agricultural chemicals. Stauffer and Wheeler decided to merge their interest. Stauffer again turned to banker de Guigne for advice and financial assistance. Not only did de Guigne encourage the merger, he decided to become part of the company. Although the shirt-sleeved, working chemists and the independently wealthy, French-born banker had very different life styles, they held identical views on thrift, integrity and the value of hard work.[iii] These values became the foundation of the company they would build. They were expressed in letters John H. Wheeler wrote to his daughter, Cornelia Wheeler Good and son-in-law Stanley Wells Good. in 1921. In those letters, John Wheeler expresses his hope that the first stock gift he gave them would be wisely managed. He planned well for his family heirs, continuing to gift them stock that would benefit generations.

In 1895, Stauffer Chemical Company was incorporated under California law, with a capitalization of $300,000. De Guigne became president, Wheeler, vice president and Stauffer, secretary. These three men ran the company for the next 37 years in great harmony and outstanding success. Ownership was retained by the families of the three founders until the company went public in 1953. Christian de Guigne gave the first chairman’s address to public shareholders.[iv]

Stauffer enjoyed growth through the 1970’s, exceeding sales of $1 Billion in 1976. Consistent with its beginnings, Stauffer’s major and most profitable business was in agricultural chemicals, although it had heavy chemical and specialty chemical divisions. The agricultural products division, along with its proprietary products and R&D, became a target of corporate raids, and in 1984, Carl Icahn made a hostile acquisition move to take over Stauffer. Meanwhile, Morley had been in discussions with the Chesebrough-Ponds Company, also a takeover target, to combine the two companies should a hostile bid be made for either company. In essence, Chesebrough-Ponds became a “White Knight” for Stauffer. White knights are preferred by the board of directors (when directors are acting in good faith with regards to the interest of the corporation and its shareholders) and/or management as in most cases as they do not replace the current board or management with a new board, whereas, in most cases, a black knight will seek to replace the current board of directors and/or management with its new board reflective of its net interest in the corporation’s equity. Icahn backed off but a new black knight, BASF of Germany, came forward. Chesebrough-Ponds acquired Stauffer in 1985 but then it, too, was acquired by Unilever in 1986.

Mr. Morley shared much of the Stauffer story with David E. Good, John Wheeler’s great grandson, while at the Summer Encampment at the Bohemian Grove in 2015. Morley is a member of Sunshiners Camp, which at one time had many Stauffer Chemical Company executives as members, including John and Rollo Wheeler.

Howard Good, John Wheeler’s grandson, held onto one share of Stauffer stock. He and many other family members were beneficiaries of a man who dared experiment in a small plant in Berkeley over a century ago, and left a lasting legacy of hard work, vision and character for those who followed him.

[i] Ibid pg. 4

[ii] Ibid pg 4

[iii] Ibid pg 4

[iv] Document 56 Christian de Guigne’s first report to the shareholders as a publicly held company in San Francisco – September 2nd 1953 and in New York – September 10th 1953.

[v] Document 65 Durrant, William P. (1977). Chemical Company Report “Thanks A Billion!” Stauffer News, Westport, CT. pg.14

St. John’s Episcopal Church, Ross

Coming soon!

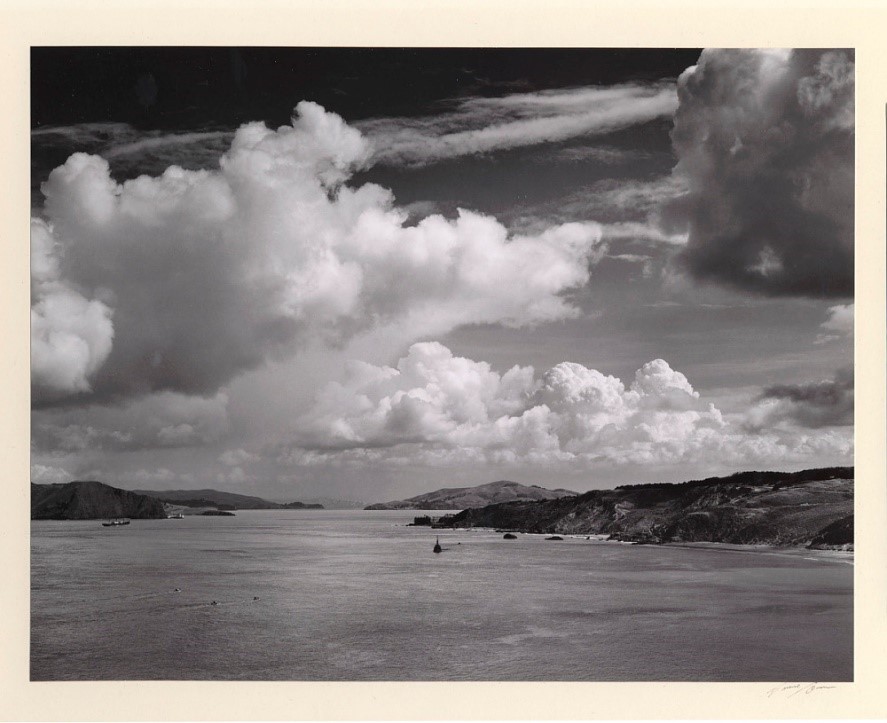

Spanning the Gate

The Golden Gate Bridge is an iconic suspension bridge spanning almost two miles across the Golden Gate, the narrow strait where San Francisco Bay opens to meet the Pacific Ocean. It is named for the Golden Gate Strait- the narrow, turbulent, 300-foot-deep stretch of water below the bridge that links the Ocean on the west to San Francisco Bay on the east. It sits 220 feet above the water with towers reaching 746 feet. Its original weight totaled 894,500 tons. Frommer’s travel guide describes the Golden Gate Bridge as “possibly the most beautiful, certainly the most photographed, bridge in the world.”

In 1846, when soldier, explorer and future presidential candidate John C. Fremont saw the watery trench that breached the range of coastal hills on the western edge of otherwise landlocked San Francisco Bay, it reminded him of another beautiful landlocked harbor: the Golden Horn of the Bosporus in what is now Istanbul. Fremont used a Greek term to name it: Chrysopidae – in English, Golden Gate. The name stuck.

Following the Gold Rush boom that began in 1848, speculators realized that the land north of San Francisco Bay would increase in value in direct proportion to its accessibility to the city. Twenty years later Charles Crocker, one of the “Big Four” San Franciscans who built the western end of transcontinental railroad, laid out plans for a bridge that would span the Golden Gate Strait, but the project wouldn’t be seriously considered for four decades.

From the time the city of San Francisco first reached metropolitan dimensions, people crossed the Bay exclusively by ferry. Designed primarily for pedestrian passengers, the age of the automobile overloaded it to the point of collapse. California citizens owned 44,000 autos in 1910. Nearly a decade later, that figure had risen to 600,000.

Many experts said that a bridge could not be built across the 6,700-foot strait, which had strong, swirling tides and currents, with water 372 ft deep at the center of the channel, and frequent strong winds. Experts said that ferocious winds and blinding fogs would prevent construction and operation.

Public support for a bridge took root in 1916 when a former engineering student and local journalist, James Wilkins, called for a suspension bridge at a cost of $100 million. San Francisco’s city engineer, Michael O’Shaughnessy, began asking bridge engineers whether they could do it for less. Engineer Joseph Strauss, a 5-foot tall Cincinnati-born Chicagoan, said he could. Strauss had, for his graduate thesis, designed a 55-mile-long (89 km) railroad bridge across the Bering Strait. He had completed some 400 drawbridges—most of which were inland—and nothing on the scale of the new project. Nonetheless, O’Shaughnessy and Strauss concluded they could build a pure suspension bridge within a practical range of $25-30 million. Engineers produced the basic structural design, introducing a “deflection theory” by which a thin, flexible roadway would flex in the wind, greatly reducing stress by transmitting forces via suspension cables to the bridge towers.

The dream of connecting San Francisco to its northern neighbors gained further momentum in 1923 when the state legislature passed the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District Act for the purpose of planning, designing, and financing construction. By August 1925, the people of six Bay Area counties agreed to join the district and pledged their homes and businesses as collateral for securing funds. A bond issue was passed in 1930 to raise $35 million, but this was the era of the Great Depression. The District was unable to sell the bonds until 1932, when Amadeo Giannini, the founder of San Francisco–based Bank of America, agreed on behalf of his bank to buy the entire issue in order to help the local economy.

Construction commenced on January 5, 1933, with the excavation of 3.25 million cubic feet of dirt to establish the bridge’s 12-story-tall anchorages. The attempt to build what would be the first bridge support in the open ocean proved an immense challenge. As a 1,100-foot trestle extended off the San Francisco side, divers plunged to depths of 90 feet through strong currents to blast away rock and remove detonation debris. When the towers were completed in June 1935, the New Jersey-based John A. Roebling’s Sons Company was tapped to handle the on-site construction of the suspension cables. The Roebling engineers, who had worked on the Brooklyn Bridge, had mastered a technique in which individual steel wires were banded together in spools and carried across the length of the bridge on spinning wheels. When completed, the two main suspension cables used a combined 80,000 miles of wire. Looped around the Earth’s equator in a single strand, it would circle the planet three times. The cable work was completed in the spring of 1936.

Howard Good began working as an engineer on the bridge cable in 1935. Years later, he would comment that the conditions, above and below the water, were harsh. The Bay Area is home to several microclimates that produce notoriously wide variations in temperature, winds, and fog. So, for the men working literally out in the ocean, hundreds of feet in the air, wild weather was inevitable. “You put all the clothes on you had and worked, worked hard, or you’d freeze. Sometimes the men would stuff newspapers in their coats for extra warmth”. Also, the height. “At 746 feet, the towers were not for the faint of heart”.

When it came time to begin construction of the bridge’s roadway, Strauss lobbied hard and won approval for a safety net that would go underneath the emerging roadway. At $130,000 dollars, it was a precious sum during the Great Depression. The safety net grew as the roadway grew, extending 10 feet beyond the width of the roadway to protect the workers. Nineteen men accidentally tumbled into the net, each cheating death. They called themselves the Halfway-to-Hell Club. Considering the hazardous and physically demanding conditions, only 11 workers died during the bridge’s construction.

The paint used on the Golden Gate Bridge is specially formulated to protect the bridge from the danger of rust from salt spray off the ocean, and from the moisture of the San Francisco fog that frequently rolls in from the Pacific Ocean. The navy was concerned about the visibility of the bridge in foggy situations so it would be noticeable for ships. But the steel that arrived in San Francisco had a burnt red and orange shade primer, which the architect preferred because it complemented the natural surroundings and contrasted well with the cool blues of the bay and the sky. The color was called “international orange”. As an added benefit, the color is highly visible in fog.

The Golden Gate Bridge was completed in May of 1937. It took a little over four years to build at a cost of $35 million. When the bridge was opened, San Francisco feted it for a solid week. Irving Morrow romanticized the Golden Gate when he wrote that the narrow strait “is caressed by breezes from the blue bay throughout the long golden afternoon, but perhaps it is loveliest at the cool end of the day when, for a few breathless moments, faint afterglows transfigure the gray line of hills.”

San Rafael Military Academy

Coming soon!

Punahou School

Punahou School is a private, college preparatory school located in Honolulu, Hawaii. Its student body consists of about 3,760[1] students from kindergarten through the twelfth grade. Its origins go back to 1841, when it was founded as a school for the children of missionaries serving throughout the Pacific region. The land on which Punahou was built, Ka Punahou, was taken in battle by King Kamehameha I in 1795 and given to chief Kameʻeiamoku, as a reward for his loyalty. The land stayed in the chief’s family, and his grand-daughter, Liliha, gave it to Reverend Hiram Bingham, one of the first Protestant missionaries in Hawaii, who built the school.

Punahou has a rich history and a wide variety of programs. Among its famous alumni are President Barack Obama, AOL founder Steve Case and teen golf phenom Michele Wie. Punahou is recognized nationally for its academic excellence. The class of 2013 had thirty National Merit Semifinalists and five National Merit Scholars [2] . Punahou also has an outstanding athletic program- it has won more state championships than any other high school in the nation and was ranked best in the country in 2006 and 2007 by Sports Illustrated. [3]

Harriette, Stanley, Jr., and Howard Good were enrolled in the junior school at Punahou shortly after their father, Stanley Good, moved to Honolulu to open the Asian office for the Dollar Steamship Company.

Stanley and Howard joined the swim team in high school and participated on several state champion teams. Howard won the state backstroke in 1927 and 1928. To the left is a picture of the 1926 team, with Howard sitting third from the left in the front row. The captain of the team, Larry “Buster” Crabbe, is fifth from the left in the second row. Crabbe went on to become a two-time Olympic swimmer-he won the 1932 Olympic gold medal in the 400-meter freestyle swimming event. He broke into acting and played the title role in the serials Tarzan, Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers. Sitting to Crabbe’s left is Louis Kahanamoku, whose older brother, “Duke” Kahanamoku, won fame with 5 Olympic swimming medals between 1912 and 1924 but is most known for being the long-celebrated father of modern surfing.

Howard’s and Stanley’s sister, Harriette (Good-Gist), also attended Punahou Academy. Harriette is pictured below in front of Cooke Hall, Punahou’s library, in 1919, ten years after Cooke Hall was completed. Harriette’s daughter and Forrest Craig’s mother, Francis Leilani attended Punahou, as did Kristen (Good) McGovern, daughter of Anthony Good.

Cooke Hall is one of the most enduring legacies in Punahou’s history, named after the famed Cooke family whose many contributions to Hawaii, beginning with missionary Amos Starr Cooke in 1837. Cooke died in 1871, but not before he founded Castle and Cooke, one of the “Big Five” corporations that dominated the territory of Hawaii’s economy and continues to this day.[1]

Cooke Hall has a rich and storied past. In December 1941, the entire campus was taken over by the United States Army Corps of Engineers (“USACE”) to be used as a command post. The library was hastily decommissioned, books relocated to the University of Hawaii, and Cooke Library became the District engineers’ office, an administrative office, temporary sleeping quarters, and officer’s mess. The first contingent of engineers arrived at the Punahou gates about 2am on December 8th (the day after Pearl Harbor). Unaware of the engineers’ emergency authority, the night watchman initially refused them access to the building. When negotiations for the building keys bogged down, the engineers broke a pane of glass in the Cooke Library door and let themselves in. It was not until 1945 that the engineers vacated and returned the building to Punahou.[i]

In 1987, Cooke Hall underwent a $1.5 million renovation to convert the original building to its present configuration as offices for faculty and administration. In 1995, the school installed a 4 foot in diameter clock on Cooke Hall’s pediment which can be seen pictured below. This iconic clock illuminates at dusk and can be seen from most anywhere on campus. Today, Cooke Hall stands as a living testament to the values upheld by Punahou School: “A commitment to the preservation of traditions and the flexibility to adapt and reshape a space to fit evolving needs of each generation of students”.[ii]

Our family has a similar philosophy regarding tradition and heritage. This was affirmed in 1981 when Howard Good, with the encouragement of his son, Tony, and Punahou president Rod McPhee, donated lane #3 on the track field in honor of his deceased son, Stuart. The lane appears below, along with the dedication plaque.

Photos courtesy of Punahou School Archives, Honolulu, Hawai’i

[4] Personal Interview with Anthony Good

[5] [6] By Zoe Dare-Attanasio ’06 http://www.punahou.edu/bulletin/detail/index.aspx?linkid=949&moduleid=69 Retrieved June 14, 2017

Pearl Harbor

Coming soon!

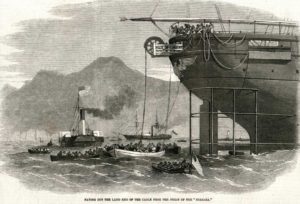

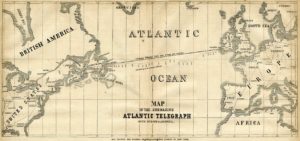

Before the first transatlantic cable was laid in 1858, communications between Europe and the Americas took place only by ship and averaged 10 days- but severe winter storms could delay ships for weeks. A transatlantic telegraph cable could reduce communication time considerably. After the major successes of the land telegraph lines on the continents, it became rapidly clear that laying a telegraph cable between the American continent and Europe would be an extremely lucrative business. But building it would require the production of a 2,000 mile long cable that would have to be laid by ship three miles beneath the Atlantic. Cyrus Field, an energetic young New Yorker wasn’t deterred, raising enough capital for the Atlantic Telegraph Co. to begin his quest. Five attempts to lay a cable were made over a nine-year period beginning in 1857. Finally, on July 27th 1866, the cable was pulled ashore by the British ship Great Eastern at a tiny fishing village in Newfoundland known by the charming name of Heart’s Content. The distance was 1,686 nautical miles, stretching from Valentia Island in western Ireland. Sent by Morse code, the first message on the 1858 cable took over 17 hours to transmit.[1]

Once the first cable was laid, many individuals and companies joined the stampede to further develop, manufacture and lay cable all over the world. Similar to the internet, computer and wireless revolution of the current day, the profitable business with the transatlantic link soon became a highly competitive market. Within 20 years, there were 107,000 miles of undersea cables linking all parts of the world.[2] From the 1850s until 1911, British submarine cable systems dominated the most important market, the North Atlantic Ocean. The British had both supply side and demand side advantages. In terms of supply, Britain had entrepreneurs willing to put forth enormous amounts of capital necessary to build, lay and maintain these cables. In terms of demand, Britain’s vast colonial empire led to business for the cable companies from news agencies, trading and shipping companies, and the British government. Many of Britain’s colonies had significant populations of European settlers, making news about them of interest to the general public in the home country.[3] The submarine cables were an economic boon to trading companies because owners of ships could communicate with captains when they reached their destination on the other side of the ocean and even give directions as to where to go next to pick up more cargo based on reported pricing and supply information. The British government had obvious uses for the cables in maintaining administrative communications with governors throughout its empire, as well as in engaging other nations diplomatically and communicating with its military units in wartime. By 1896, there were thirty cable laying ships in the world and twenty-four of them were owned by British companies.[4] In 1892, British companies owned and operated two-thirds of the world’s cables and by 1923, their share was still 43 percent.[5] During World War I, Britain’s telegraph communications were almost completely uninterrupted, while it was able to quickly cut Germany’s cables worldwide.[6]

The seven-strand conductor was initially the one most commonly used for submarine cables.[7] The core as supplied would then have to be insulated and armored to protect against abrasion from ship’s anchors, trawls and marine boring insects.[8] Technology advances rapidly improved transmission speed and reliability. While the first message on the 1858 cable took over 17 hours to transmit the 1866 cable could transmit eight words a minute 80 times faster than the 1858 cable.[9]

Okonite Company founded in 1878, specialized in the development and manufacture of cable. One of the original insulators of electrical wire and cable in the United States, its earliest customers included Samuel F.B. Morse for his telegraph network and Thomas A. Edison for the Pearl Street Generating Station, the nation’s first, built in New York City in 1882.[10] Based in New York, Okonite manufactured cable for many uses, including the Trans-Atlantic cable. John Dwyer Ashton joined the company in the 1890s and became its treasurer before leaving the company shortly after 1920.

Today, Okonite is headquartered in Ramsey NJ, approximately 30 miles northwest of New York City.“It has undergone many changes of ownership, and along the way much of what we assume existed and had historical value has been lost to the Company. In 1976 the present management, which is an Employee Stock Ownership form of management, purchased the company out of a bankruptcy proceeding in Dallas. At the time, Okonite was owned by a company called Omega-Alpha, part of LTV (Ling-Temco-Vought) Corporation. In many respects, it was as if Okonite were starting out fresh.”[11]

It was not until the 1960s that the first communication satellites offered a serious alternative to cable.

[1] Wikipedia

[2] Ibid

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid

[7] Ibid

[8] History-magazine.com

[9] Atlantic-cable.com

[10] Ibid

[11] Email from Frank Giuliano, General Counsel of Okonite Cable Company, to David Good, April, 2016.

MacArthur Place

MacArthur Place and the property and buildings which comprise it in Sonoma have a long and distinguished place in California history. Located within minutes of the Sonoma Plaza, the former Burris-Good estate is composed of beautiful gardens, majestic old trees, and historic architecture. The two-story Victorian house which dominates the property was built in the 1850s and is one of the oldest Victorian homes in Sonoma.

It was built and owned by David Burris (1824-1904), who in 1846, journeyed west from his native Missouri.[1] He and his brother initially engaged in mining at Bidwell’s Bar on the Feather River, then mined with success in Plumas County before moving to Sonoma County.[2] Burris became one of the most highly respected and wealthiest citizens of Sonoma County in the last half of the 19th century.[3] The property was a working ranch with vineyards, fruit orchards, a hay crop, cattle and many prized and well-trained trotters used for transportation in this horse and buggy era.The core of the estate was a roughly 47-acre tract bounded by Broadway (west), 3rd Street East (east), MacArthur Street (historically Germany Street, north), and Denmark Street (south).The house was constructed using wooden pegs and square nails (still fronted by the original white picket fence) and was home for his family of nine children. Burris was a founder of the Sonoma Valley Bank, conducting business out of the home’s corner library on the first floor.[4]

Five generations of the Burris family occupied the property. Over the course of the 20th century, Burris’ estate conveyed several multi-acre parcels from the main tract, reducing its size gradually. In 1921, a 12-acre portion of the 46-acre tract was conveyed by the Burris Estate to Sonoma Valley Union High School, which was followed by an additional conveyance of a 20 acre parcel to the high school in 1950, reducing the size of the tract to approximately 12 ½ acres.[5]

Leilani (“Anna”) Burris Welch was the last Burris to reside on the property. Anna was the “little sister” of Jane Lines (Good) at Mills College in Oakland in the 1930’s and the two remained close friends for life. When Anna died in 1971, her husband Garry sold the property to Jane and her husband, Howard.

The Good family enhanced the gardens, installed a paddle tennis court, constructed an eight car carport and expanded the barn.

There were many family gatherings at “Sunnyside Farms”, including paddle tennis games, riding bikes and Big Wheels, playing dominoes by the swimming pool and working the farm with Jane and Howard. A frequent visitor, especially at domino and meal time, was Col. Walter Gerdau, who had a Victorian home just up Austin Street.

In 1997, Suzanne Brangham purchased the property from the Good Estate and began creating a luxurious country inn. The property was reborn as a 64-room hotel, MacArthur Place, with a state-of-the-art conference facility, restaurant and full-service spa. Along with maintaining the original architecture on the buildings, and replicating its charm with new cottages, the beautifully planned landscaping had lush plantings, mature trees, rose gardens, a pool and spa sanctuary, a fish pond, water fountains and more than 30 original sculptures. Nathanson Creek winds along the western side of the property, creating a beautiful backdrop for visiting guests. MacArthur Place enjoyed 20 years of success under Suzanne’s and Bill Blum’s leadership. It was subsequently sold to IMH Financial Corporation in 2017.

References:

[1] Source: History of the New California Its Resources and People, Volume I The Lewis Publishing Company – 1905 Edited by Leigh H. Irvine

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.