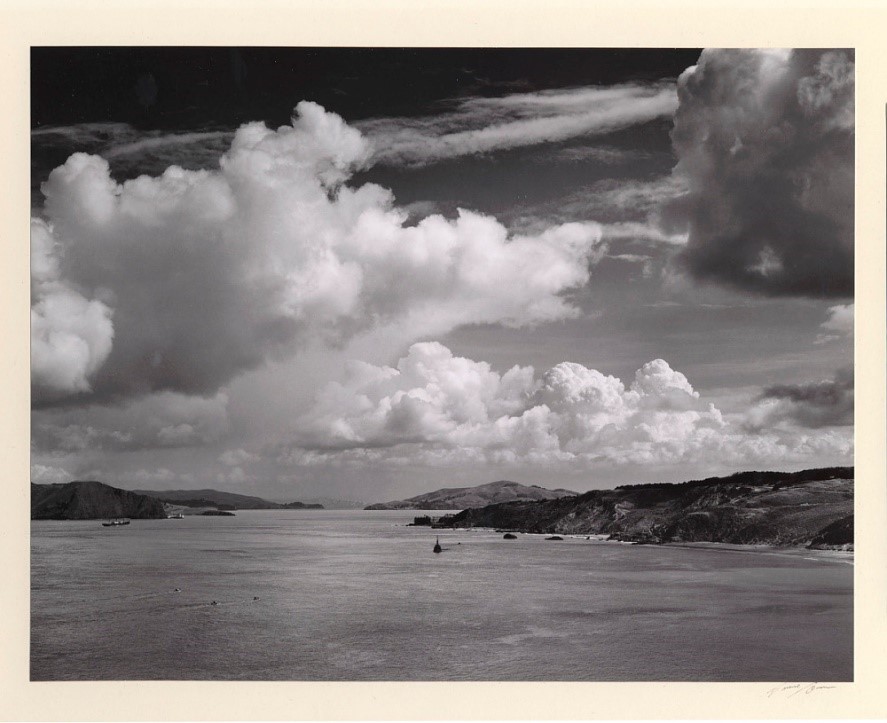

The Golden Gate Bridge is an iconic suspension bridge spanning almost two miles across the Golden Gate, the narrow strait where San Francisco Bay opens to meet the Pacific Ocean. It is named for the Golden Gate Strait- the narrow, turbulent, 300-foot-deep stretch of water below the bridge that links the Ocean on the west to San Francisco Bay on the east. It sits 220 feet above the water with towers reaching 746 feet. Its original weight totaled 894,500 tons. Frommer’s travel guide describes the Golden Gate Bridge as “possibly the most beautiful, certainly the most photographed, bridge in the world.”

In 1846, when soldier, explorer and future presidential candidate John C. Fremont saw the watery trench that breached the range of coastal hills on the western edge of otherwise landlocked San Francisco Bay, it reminded him of another beautiful landlocked harbor: the Golden Horn of the Bosporus in what is now Istanbul. Fremont used a Greek term to name it: Chrysopidae – in English, Golden Gate. The name stuck.

Following the Gold Rush boom that began in 1848, speculators realized that the land north of San Francisco Bay would increase in value in direct proportion to its accessibility to the city. Twenty years later Charles Crocker, one of the “Big Four” San Franciscans who built the western end of transcontinental railroad, laid out plans for a bridge that would span the Golden Gate Strait, but the project wouldn’t be seriously considered for four decades.

From the time the city of San Francisco first reached metropolitan dimensions, people crossed the Bay exclusively by ferry. Designed primarily for pedestrian passengers, the age of the automobile overloaded it to the point of collapse. California citizens owned 44,000 autos in 1910. Nearly a decade later, that figure had risen to 600,000.

Many experts said that a bridge could not be built across the 6,700-foot strait, which had strong, swirling tides and currents, with water 372 ft deep at the center of the channel, and frequent strong winds. Experts said that ferocious winds and blinding fogs would prevent construction and operation.

Public support for a bridge took root in 1916 when a former engineering student and local journalist, James Wilkins, called for a suspension bridge at a cost of $100 million. San Francisco’s city engineer, Michael O’Shaughnessy, began asking bridge engineers whether they could do it for less. Engineer Joseph Strauss, a 5-foot tall Cincinnati-born Chicagoan, said he could. Strauss had, for his graduate thesis, designed a 55-mile-long (89 km) railroad bridge across the Bering Strait. He had completed some 400 drawbridges—most of which were inland—and nothing on the scale of the new project. Nonetheless, O’Shaughnessy and Strauss concluded they could build a pure suspension bridge within a practical range of $25-30 million. Engineers produced the basic structural design, introducing a “deflection theory” by which a thin, flexible roadway would flex in the wind, greatly reducing stress by transmitting forces via suspension cables to the bridge towers.

The dream of connecting San Francisco to its northern neighbors gained further momentum in 1923 when the state legislature passed the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District Act for the purpose of planning, designing, and financing construction. By August 1925, the people of six Bay Area counties agreed to join the district and pledged their homes and businesses as collateral for securing funds. A bond issue was passed in 1930 to raise $35 million, but this was the era of the Great Depression. The District was unable to sell the bonds until 1932, when Amadeo Giannini, the founder of San Francisco–based Bank of America, agreed on behalf of his bank to buy the entire issue in order to help the local economy.

Construction commenced on January 5, 1933, with the excavation of 3.25 million cubic feet of dirt to establish the bridge’s 12-story-tall anchorages. The attempt to build what would be the first bridge support in the open ocean proved an immense challenge. As a 1,100-foot trestle extended off the San Francisco side, divers plunged to depths of 90 feet through strong currents to blast away rock and remove detonation debris. When the towers were completed in June 1935, the New Jersey-based John A. Roebling’s Sons Company was tapped to handle the on-site construction of the suspension cables. The Roebling engineers, who had worked on the Brooklyn Bridge, had mastered a technique in which individual steel wires were banded together in spools and carried across the length of the bridge on spinning wheels. When completed, the two main suspension cables used a combined 80,000 miles of wire. Looped around the Earth’s equator in a single strand, it would circle the planet three times. The cable work was completed in the spring of 1936.

Howard Good began working as an engineer on the bridge cable in 1935. Years later, he would comment that the conditions, above and below the water, were harsh. The Bay Area is home to several microclimates that produce notoriously wide variations in temperature, winds, and fog. So, for the men working literally out in the ocean, hundreds of feet in the air, wild weather was inevitable. “You put all the clothes on you had and worked, worked hard, or you’d freeze. Sometimes the men would stuff newspapers in their coats for extra warmth”. Also, the height. “At 746 feet, the towers were not for the faint of heart”.

When it came time to begin construction of the bridge’s roadway, Strauss lobbied hard and won approval for a safety net that would go underneath the emerging roadway. At $130,000 dollars, it was a precious sum during the Great Depression. The safety net grew as the roadway grew, extending 10 feet beyond the width of the roadway to protect the workers. Nineteen men accidentally tumbled into the net, each cheating death. They called themselves the Halfway-to-Hell Club. Considering the hazardous and physically demanding conditions, only 11 workers died during the bridge’s construction.

The paint used on the Golden Gate Bridge is specially formulated to protect the bridge from the danger of rust from salt spray off the ocean, and from the moisture of the San Francisco fog that frequently rolls in from the Pacific Ocean. The navy was concerned about the visibility of the bridge in foggy situations so it would be noticeable for ships. But the steel that arrived in San Francisco had a burnt red and orange shade primer, which the architect preferred because it complemented the natural surroundings and contrasted well with the cool blues of the bay and the sky. The color was called “international orange”. As an added benefit, the color is highly visible in fog.

The Golden Gate Bridge was completed in May of 1937. It took a little over four years to build at a cost of $35 million. When the bridge was opened, San Francisco feted it for a solid week. Irving Morrow romanticized the Golden Gate when he wrote that the narrow strait “is caressed by breezes from the blue bay throughout the long golden afternoon, but perhaps it is loveliest at the cool end of the day when, for a few breathless moments, faint afterglows transfigure the gray line of hills.”